January 13, 2022

January 13, 2022

Original article published in Inside Climate News

The battery economy is booming, and with it a recycling industry is bracing itself for a wave of battery waste.

Battery Resourcers of Worcester, Massachusetts, said last week that it is planning to build a plant in Georgia that will be capable of recycling 30,000 metric tons of lithium-ion batteries per year. It will be the largest battery recycling plant in North America when it opens later this year.

But its reign will be brief because Li-Cycle, based in the Toronto area, is building an even larger battery recycling plant near Rochester, New York, that is scheduled to open in 2023. The company said last month that it is modifying its plans in a way that increases the plant’s size, a response to forecasts of high demand for recycling.

To help understand what’s happening, I reached out to Jeff Spangenberger, a researcher at Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois and also director of the ReCell Center, a collaboration between the government and industry to improve battery recycling technologies.

“If the process is good enough, there’s no reason why you can’t make battery materials from the battery materials,” he said.

For him, the development of a battery recycling industry is one of the most important and exciting parts of the transition to clean energy.

It’s important because the growth of electric vehicles and battery storage systems will eventually lead to millions of tons of batteries that are unusable unless they are recycled. And it’s exciting because researchers and entrepreneurs are coming up with cost-effective ways to reuse most of that waste.

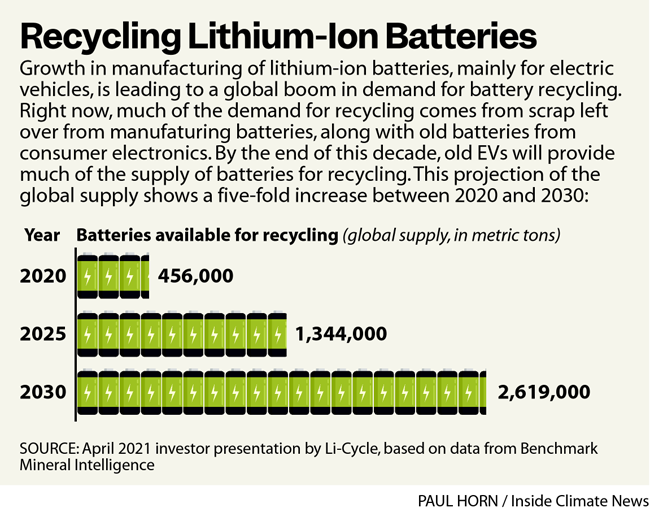

The recycling industry is changing and growing to prepare for a projected five-fold increase in the amount of lithium-ion batteries available for recycling globally by 2030, according to figures from Li-Cycle and Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

Lithium-ion batteries are used to power electric vehicles, battery storage and consumer electronics. The batteries contain rare and expensive metals like cobalt and nickel.

As companies manufacture more batteries, governments and environmental advocates have growing concerns about environmental damage from across the battery lifecycle, including the mining of metals to manufacture batteries, and the pollution that happens when old batteries end up in landfills.

Researchers and entrepreneurs want to use recycling to reduce the need for mining and reduce waste when batteries reach the end of life.

Battery recycling is not new. Companies have processed batteries and other electronic waste for decades. Even with advances in technology, the front end of the process hasn’t changed much, with workers standing over a conveyor belt of old batteries that they feed into a shredding machine.

Lithium-ion batteries often reach the end of their lives because they have degraded following years of charging and discharging, which leads to small physical changes that gradually reduce their capacity for holding a charge, not because metals inside are no longer usable.

The recycling process often begins by separating out the plastic covering and bits of copper and aluminum foil, leaving a material called “black mass,” a powdery black substance that makes up most of the guts of the battery. The black mass contains cobalt, nickel and lithium, along with graphite and other substances.

The hard part, and the essence of the technologies the businesses have developed, is processing the black mass to extract the valuable materials and remove impurities so the materials can function like new.

Battery Resourcers is a privately held company, founded in 2015, that grew from a project at Worcester Polytechnic Institute and has a small plant in Worcester. The company is planning to spend $43 million and hire 150 workers at the Georgia plant, which would open in August.

“This is just the start of a huge recycling infrastructure,” said Roger Lin, vice president of marketing and government relations for Battery Resourcers, in an interview. “We feel we have a very efficient and clean process to make the battery economy truly circular, and that’s why we’re excited with what we’re doing in Georgia and beyond.”

When he talks about a circular economy, he is referring to a set of principles and policies that aim to reduce waste and find ways to continually reuse resources rather than extracting them from the earth.

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp hailed the company’s announcement, saying Battery Resourcers was the latest to move to the state “because of our leadership position in the electric vehicle manufacturing space.”

Indeed, Georgia is becoming a hub of the battery economy. One high-profile example is Rivian, the EV truck maker, which said last month that it will build a plant near where the Battery Resourcers plant will be located, east of Atlanta. Battery Resourcers has declined to comment on whether it will be working with Rivian.

As the recycling industry grows, it also needs to convince battery manufacturers that recycled materials can meet the same performance standards as mined materials. Yan Wang, a professor at Worcester Polytechnic and a co-founder at Battery Resourcers, was part of a team that published an analysis in the journal Joule last year showing that recycled materials can outperform new materials in physical tests and simulations.

This was just one paper, but its findings were in line with what recycling companies say they expect to see as they continue to learn and improve.

Li-Cycle, based outside of Toronto, has small plants in Kingston, Ontario, and near Rochester, New York, and is building the much larger plant near Rochester with a projected cost of $175 million. The larger plant would be able to process 35,000 metric tons of black mass per year, which the company says is equivalent to about 90,000 metric tons of lithium-ion batteries.

The company, founded in 2016, is developing a system of small plants that do initial processing of batteries and then feed into regional hubs like the one being built near Rochester. This is part of a long-term plan, through expansion and joint ventures, to have small plants and regional hubs covering the world’s major EV markets, including in China.

Li-Cycle went public last year and has a market capitalization of $1.45 billion. The company has said its process can recover about 95 percent of the materials in a lithium-ion battery, and do so without producing wastewater and with minimal air emissions.

Like so much in the clean energy economy, China is way ahead of the United States, leading the world in battery manufacturing and recycling. The ReCell Center and others are trying to jumpstart a U.S. industry so that batteries from old EVs don’t need to be shipped to China one day for recycling.

China-based CATL is the largest battery manufacturer in the world. It has a subsidiary, Brunp Recycling, with capacity to recycle 120,000 tons of batteries per year.

CATL said in October that it was planning to spend the equivalent of $5 billion to build a new recycling plant in the Chinese province of Hubei.

“We’re behind,” said Spangenberger, about competition with China. “But we’re picking up speed.”